Online fandom can be a community, but it can also be a combat sport. It goes all the way back to the early stages of social media: There were the deep dives into Pete Wentz’s LiveJournal (RIP) to find out what was happening with Fueled by Ramen and Fall Out Boy. There was Tumblr during the Skins Freddie/Effy/Cook love triangle. There were the Facebook groups dedicated to each Jonas brother. At the time, it felt like fandom in its highest form. But in hindsight, Joe vs Nick feels like child’s play in comparison to the fandom wars of today.

As algorithms have evolved to feed off of our identities, the internet has become an increasingly divisive space. To “stan” Taylor Swift is no longer enough; you have to be against anyone or anything that a louder Swiftie has deemed a threat. Selenators are known to weaponize other celebs’ comments sections. Sometimes, it’s almost like the fandom is less about sharing in the expression of what you love and more about drawing lines in the sand. You’re with “us” or you’re against us—and we’re against you. This sentiment, it seems, is the black-and-white hallmark of 2010-2020 fandoms.

Conversely, in recent years, we’ve also seen fandom emerge in healthier ways. Those same Swifties are connecting lifelong stans and casual Eras Tour attendees alike with optimistic friendship bracelets. Wicked fans are painting themselves equal parts green or pink without any “Team Glinda” or “Team Elphaba” discourse. Fandoms aren’t always about drawing that line in the sand. They can also be connective, comforting, and a non-serious form of joyful expression.

But the line is thin.

The Good

@charli_xcx / Instagram

Good fandom, to me, is an identity expression that expands you, not protects you. Feeling isolated and lonely is a pretty common feeling, but there are thousands of places for people to find community in a mutual shared love and interest (it’s basically the general premise of why Reddit exists). There’s something for everyone in these spaces, and they can often morph into opportunities and experiences unlike anyone can imagine. Famously and far more commonly than ever, fan fictions have turned into novels, and those novels have been adapted into movies. Lionsgate hired TikTok fan editors to work on their marketing teams. Charli XCX gave us Brat summer and we are still longing for it more than a year later. There is something wonderful about collective joy and being able to turn your admiration into another form of being. Not only that, but in a day and age of increasing cynicism or fear of appearing “cringe,” it’s just nice to really like something and not be afraid to share that with others.

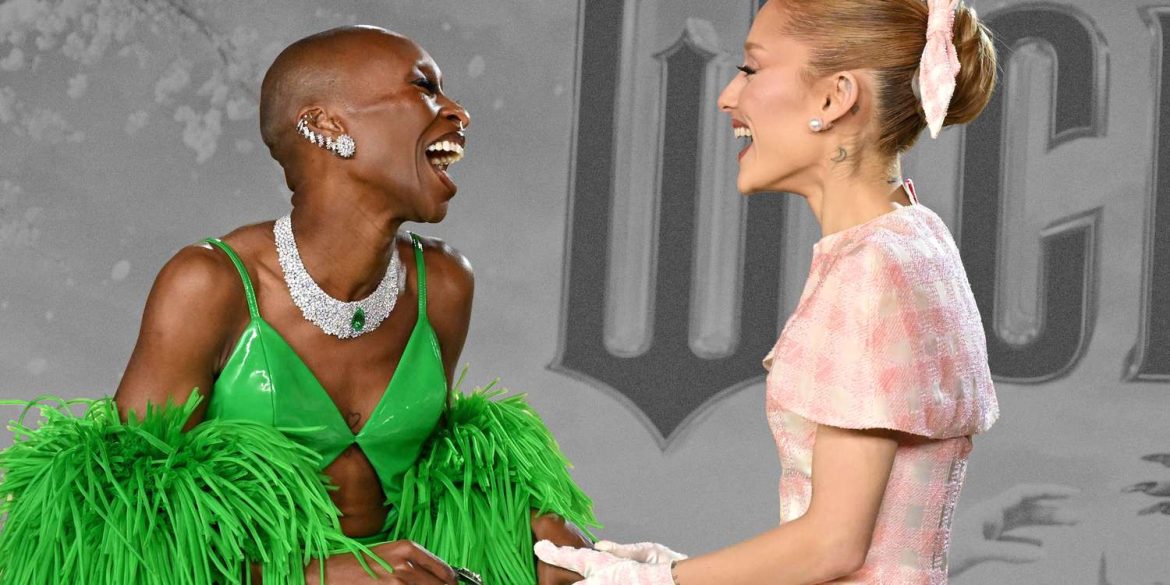

I’d argue that’s why Wicked has had such resonance with audiences. As a reluctant theatre kid, I’ve known long about theatre fandoms, but even the Wicked conversation revolves more about who your personal preferred Elphaba and Glinda are from the Broadway production. The Wicked fandom celebrates both Ariana Grande and Cynthia Erivo equally, because this is about collective excitement, not rivalry.

Getty

Some actually first fell in love with Wicked when it first debuted in 2004, and those fans aren’t flooding comments sections with vitriolic statements about being here “first” or “earning” the right to enjoy the film. Instead, they’ve embraced the new fans and mainstream status because that’s the point of the musical—empathy, chosen family, and shared joy. Wicked is an anomaly in fandom culture because it fundamentally rejects binary thinking—it’s not Team Glinda vs Team Elphaba.

Wicked is an anomaly in fandom culture because it fundamentally rejects binary thinking…”

The thesis of the story is that perspectives are complex, people contain multitudes, and “villains” often aren’t what they seem. Having seen antihero narratives play out in other fandoms—Breaking Bad comes to mind—it just stands to show that this narrative can be understood in the grey area. (It just might have to be sung through in the land of Oz.)

The Bad

The “Team X vs Team Y” level of binary thinking has led to death threats amongst many other things, as if this fictional character (or real celebrity) can’t fight their own battles. This type of toxic fandom typically uses harassment as a disguise for loyalty, whilst robbing the object of their standom of most forms of agency. This person does not know you exist, or they may not even exist themselves—not every action is worthy of deep analysis. To critique is to blaspheme, and we’ve seen punishments of said blasphemy taken to extreme levels over the years.

Take the Selena Gomez and Hailey Bieber discourse on Reddit, for example. Despite the two having publicly vocalized support of one another (and so much as taken a photo together), fans of both individuals are still displaying a concerning level of tribalistic behavior. Fans projecting narratives the celebrities themselves publicly reject is a major sign of toxic standom.

Fans projecting narratives the celebrities themselves publicly reject is a major sign of toxic standom.”

It doesn’t matter what they say, because the stans insist they can read between the lines and find the “Easter eggs.” Once you’ve reached the public eye, none of your words or behaviors belong to you when it comes to your stans. Charli XCX encapsulated this invasive feeling of toxic standom on “Guess”, when she referenced the 2017 hacking and leaking of her Google Drive demos with the lyric “You wanna guess the password to my Google Drive / You wanna guess the address of the party I’m at”. The moment your love for something becomes a hill you’re prepared to die on or invade someone’s privacy for, you’re no longer a fan—you’re an entitled foot soldier. You don’t want to be the kind of fan who is so toxic that the thing you love becomes synonymous with a toxic fan base and thus, a barrier to entry for new fans.

The Pursuit of Unproblematic Fandom

Whether it’s sports, a musician, a YouTube channel, the 2025 revival of Sunset Boulevard (whoops, that’s mine), it’s positively wonderful—and human in the best way—to be excited about something. There’s a way to be a part of all the joy and self-affirmation that fandom has to offer without tap dancing into toxicity. Here, I’ve included a self-check list of questions to consider if you’re worried the House of Toxic Fandom™ is asking you to move in.

- “Do I actually love this thing, or am I just defending it online like it pays my rent?”

- “Do I feel personally attacked when someone critiques my favorite artist/show/movie?”

- “Would I act this way in public? At work? In front of my therapist?”

- “Does being in this fandom make me bigger, or smaller?”

- “Is this community expressive—or am I just performing allegiance?”

- “Could I take a 48-hour break without experiencing withdrawal?”

Getty

And finally and foremost: “Who asked me to do this?” The phrase “touch grass” can feel overused, but never has it been more relevant. It’s okay to take breaks, it’s okay to not be the #1 fan in the world. Just being a fan is enough for anyone who is creating something to be enjoyed by the public, there’s not a hierarchy or a tiered section. It’s called “identity fusion” when a person merges their sense of self with a group or figure. Remember that not everyone knows everything you know and that you’re still interacting with humans at the end of the day. Staying open and empathetic is key.

Truly, fandom isn’t inherently good or bad—it’s about how we use our love and admiration. You can be a part of a fandom that’s collaborative, empathetic, and built around shared excitement. Creativity should be a tool for connection, not competition, and anyone should have access to enjoyment. It shouldn’t have to exist in the binary, despite the massive amounts of messaging we receive to the contrary.

At its best, fandom doesn’t ask you to pick a side — it hands you a broom, paints you green, and says, “Come join us. There’s plenty of magic to go around.”